Missing Stephen

I was invited to teach a class at Keuka College. I used to be on the faculty there so it was something of a return for me. Although I thoroughly enjoy what I do, I have to admit that I miss teaching.

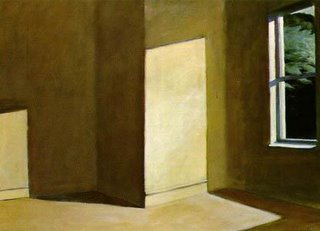

I was invited to teach a class at Keuka College. I used to be on the faculty there so it was something of a return for me. Although I thoroughly enjoy what I do, I have to admit that I miss teaching.The students were leaving the room, and I sat in the front of the class as is my custom and I watched them as they moved on with their day. Then they were all gone. As I turned out the lights in the room where the students had been just a few moments earlier, I felt a little sadness that I was alone. I considered how the room had been busy and full of chatter and even some excitement. We were learning about evidence based practice and early intervention.

As I sat alone in the room, on a mat table in the corner, I remembered Stephen.

Stephen was probably the most learning disabled child I have ever worked with. This will undoubtedly be very difficult for anyone to understand who does not know about learning disabilities. These kids walk and talk and superficially appear just like every other kid. There is no wheelchair to set them apart, and no disfigurement. As a result, some people doubt that they really have problems at all or will simply attribute their problems as 'behavioral.' Also, there are many different types of learning difficulties, and this only confuses the situation.

I worked with Stephen when he was six years old, and last I saw him he was about eight. Stephen had such a difficult time when learning new tasks. For a while I strongly considered that he was mentally retarded, but every time he was tested he was found to be functioning in a scattered range of capabilities - but that he was NOT mentally retarded.

Working with Stephen was so hard and frustrating to us both that on bad days I secretly hoped that someone would tell me that he was unteachable. That would get me off the hook, and then I could stop trying to remediate the problem and work more on compensating and advocating around it. But this relief never came.

Stephen had to be taught EVERYTHING. He was as literal as a person could be, and he had no concept of abstractions in language. He had such poor motor skills that I actually had to teach him how to eat soup with a spoon, had to teach him how to put on a coat, and I even had to teach him how to wipe himself after going to the bathroom. With Stephen there was no such thing as intuitive.

You can imagine the disability that this degree of difficulty causes. Concomitantly, you might imagine the degree of purity of Stephen's soul. He had no blemishes, and since so little stuck into his memory banks and became the basis for further and future processing, his demeanor was as pure and as innocent as any person I have ever met in my life.

When Stephen came for therapy, he would expect me to be in the room waiting for him, sitting on the red mat table. When he entered the room I would see a large smile appear across his face and I would smile right back at him, yelling "Stephen!!! You're here!!!" This always caused him to come and give me a big bearhug hello.

I enjoy watching children think. I like the way that they pause thoughtfully before they ask questions. One day while we were working on puzzles he asked me, "What do you do when I am not here?" I shot back immediately, "I wait until you come back." The answer didn't seem to surprise him at first, but after several minutes he persisted, "You must go home. I know that you have a family probably." Seeing this as an opportunity for grand fun, I insisted, "Stephen, when you leave, I go right to that mat table and sit, waiting for you to come back again."

This concept intrigued and amazed him. Each time that he came in I would be sitting on the mat table waiting for him. He only came twice a week, but I always had my secretary warn me that he was coming so that I could assume my place on that red mat table.

Up until the last day I saw him, Stephen was convinced that the sole purpose of my life was to play with him twice a week and talk to him about the things that were hard for him to do, and to teach him strategies on how to make those things easier. He would leave the room, and as I sat on the mat, I would ask him to turn out the lights for me, and I told him that I would be waiting 'right here' for when he would come back.

After a while, when watching him leave, seeing those lights turn off, I imagined that Stephen was the sole purpose of my life. And it made me sad when he left.

I remembered that today. And I missed Stephen.

Comments