On behavior intervention plans and the carceral archipelago

It is critical for occupational therapists to understand the nature of power relationships and control mechanisms when they are working with children or adults who have disabilities. I understand that I can take steps beyond what I will express here – and begin a discourse on the very nature of identifying the concept of disability – but I want to ignore those larger issues and instead focus on the relationships between those who are already identified as ‘disabled’ and those identified as ‘normal.’ So for the purposes of this discussion, we will overlook the discussion that ‘medicalization’ creates power differentials and supports social control in itself.

It is critical for occupational therapists to understand the nature of power relationships and control mechanisms when they are working with children or adults who have disabilities. I understand that I can take steps beyond what I will express here – and begin a discourse on the very nature of identifying the concept of disability – but I want to ignore those larger issues and instead focus on the relationships between those who are already identified as ‘disabled’ and those identified as ‘normal.’ So for the purposes of this discussion, we will overlook the discussion that ‘medicalization’ creates power differentials and supports social control in itself.I am not an ivory tower academic. I am just a street-level occupational therapist who is trying to do a good job and to appropriately serve the people who ask me for help. I mention this because if anyone reads this I want them to know that my interest is grounded in the tasks I am asked to do everyday. This is very real to me – it is not an academic exercise.

Stories offer us a mechanism for understanding something about experience; they are meant to be both evocative and provocative (Mattingly & Garro, 2000, pp. 10-11). They also are supposed to “offer a powerful way to shape conduct because they have something to say about what gives life meaning… compelling stories move us to see life… in one way rather than another.” Here is the story that brings this to the forefront of my thinking:

Shannon was born with cerebral palsy and she has a mild degree of mental retardation. These conditions cause obvious functional impairments and she has always been eligible for special education services. Murphy (1990) states that being disabled is the same as being relegated to permanent liminality. This is mostly true for Shannon. She could walk and talk – but with a limp and a slur. She didn’t learn as quickly as the other students. She has seen and understood her lack of competence for her entire life. This was reinforced by her placement in special classes and by the lack of inclusion when her age-mates called all the other children in the class to invite them to a birthday party. Shannon stayed home those days, and her mother probably comforted her. This is a common theme for many children who have developmental disabilities.

Both of Shannon’s parents died when she was just twelve. There were no other relatives who could care for her, so she entered foster care. She lived in a multitude of homes, each placement being less successful than the previous one.

Over time it was determined that in addition to cerebral palsy Shannon also had oppositional defiant disorder. And conduct disorder. And adjustment disorder. And post traumatic stress disorder. There are some others too. Shannon’s behavior was becoming unmanageable.

There was a need to control Shannon’s behavior. Her chart outlined all the concerns, indicating that she could be manipulative and demanding. To control the behaviors a plan was put into place.

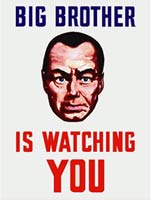

Behavior plans are written for the staff who wield ultimate power and provide a panopticistic strategy for managing the people in their charge. By definition they are generally reductionistic and arguably dehumanizing. Shannon’s plan went into detail about her temper tantrums and sexual precocity; it failed to mention that her parents died when she was just entering adolescence. Instead, the plan stated that “behavioral problems seem to be related to the transition from school, the bus ride, and entrance into the high school after attending the morning vocational program.”

Shannon had a reward program where she could earn tokens for positive behavior. She could earn ten tokens a day. Thirty tokens bought her two pencils. Sixty tokens bought her a candy bar. A hundred tokens bought her a fifteen minute conversation with a favored teacher, who she loved. Two hundred fifty tokens bought her a ‘date’ with a favored residential staff member, who would arrange to take her somewhere special.

Yes, the only things she truly valued and loved had to be purchased, coercively, with tokens. Ten days of good behavior bought her a brief nurturing conversation. Twenty five days of good behavior bought her individualized contact with the only semblance of family that was available. Hope is critical for people who face extreme adversity (Spencer, Davidson, & White, 1997). I can’t imagine that anyone could muster up much hope under these circumstances.

I expect that the behavior plan was written with good intentions, but I am very worried that too many professionals with good intentions make horrible mistakes. Occupational therapists should continue to study these stories so that they can develop a deeper understanding of illness experiences and be in a better position to help participate in humane care for people who have developmental disabilities.

References:

Mattingly, C., & Garro, L. C. (2000). Narrative and the cultural construction of illness and healing. Berkley, CA: University of California Press.

Murphy, R. (1990). The Body Silent. New York: W.W.Norton.

Spencer, J., Davidson, H., & White, V. (1997). Helping clients develop hope for the future. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51, 191-198.

Related reading:

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). New York: Pantheon Books. (original work published 1975).

Comments